2025-10-09

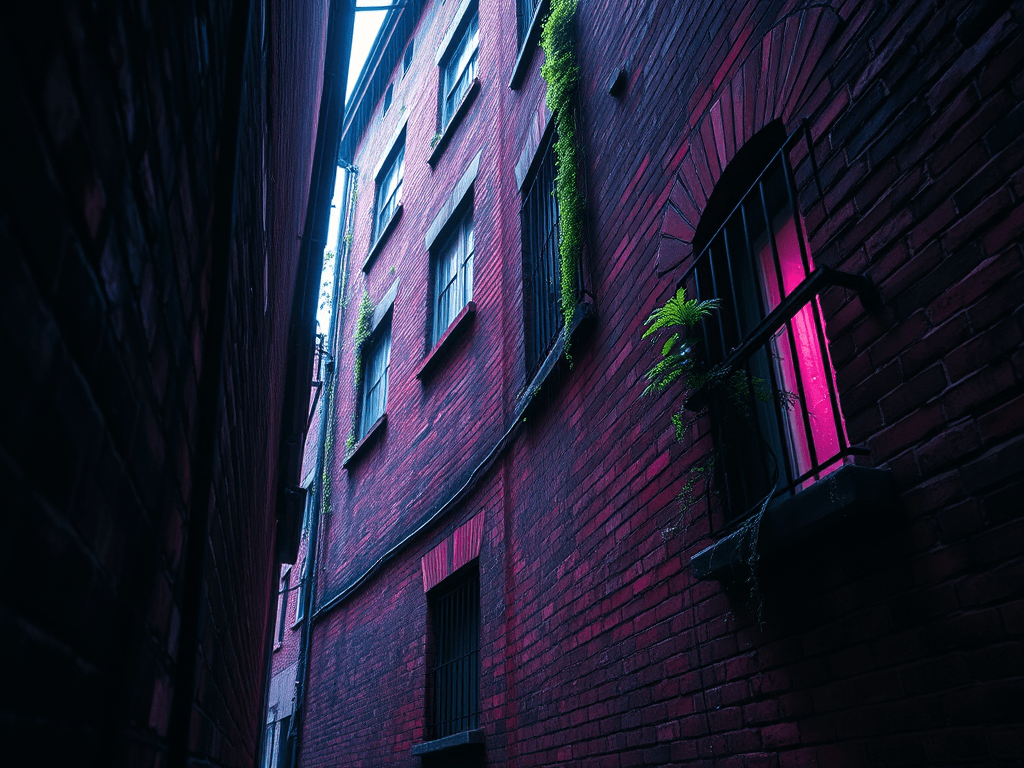

My destination is down eight steps, off a narrow alley, in the tired part of a town where the work disappeared fifty years ago and not everyone followed. There are a lot of places like this, we’re a nation of them. They’re the remains of better times, when our parents grew gold and everyone was buying. My favourite is a brick master, four or five stories. The maroon rectangles are stained, pocked, and higgledy-piggledy, with all the straight lines crooked and bent. A fern grows in one hole. Lines of moss grow down from others. Inside, through barred windows, I’ve seen timber beams cloaked in grey, and motes that dance through clear light or rusted out holes; little maws open to the rain.

I make it five steps down the alley before I turn around. I finger the card in my hands, swallow, and pick up my pace. I can’t do it. My legs ache and my hips burn. They laugh at me.

That night, I follow my ritual, filling and then emptying the fridge, transferring brown and green to my hand, then the bin outside. When I wake up there’re two sets of glares. The first disappears quickly; from shame or pity, I’m not sure. I have to leave the house either way. But I can’t escape the other glare, it’s in the sky.

A few hundred a week isn’t a lot. Aches and pains take a good bit. Rent a good bit more. Plus power’s going skywards, food’s already up, and my ritual has never been harder to make. So I do what I can, I shovel brown into bags, box it up, and help ‘em send it away. It’s not hard work, but they make it harder for me. It’s always good morning, how’re things, did you see—, and so on. And on. And on. A little quiet shouldn’t be too much to ask for, but it is. And so I murmur something back and watch as their eyes slide away from mine and their care is revealed for the thin sheet it is.

Some office-type comes in to watch. Tells me I’m doing it wrong. Tells me that I should do it like this. As though I can. As though I haven’t tried. Their plastic coat and blue overboots are the only ones in the room of cotton whites and white gumboots. The only false ghost here.

It rains today, after my shift ends. Good northern rain, thick globules that tear through the air sideways and smack into the dust. I snatch the office man’s plastic coat from a waste-bin, and go out, feeling the drops spatter against the layer. I cross the yard, where dust is giving way to mud, and pull out my key for the door. Inside, the car still stinks from damp the last time water got into the boot. And so the cycle continues.

On my way home, I stop. I make it ten steps down the alley before I turn around. I finger the card in my hands and feel the edges against my fingers. I shake my head.

No glares this morning. Yesterday’s rain continues, and she’s gone to work. Toilets and showers and dirty floors are eternal, and she knows it. There’s a note telling me to put the glass out, as it’s too heavy for her. So I do, and pretend it isn’t too heavy for me.

They don’t call me into the plant, so I don’t go. Instead I lie on the bed and look at the ceiling. When that gets too much, I roll over and close my eyes. When that gets too much, I open the draw and pull out my photos.

I was young, once. Dark hair and dark eyes, with dark skin and white teeth to boot, looking at the camera with a beach behind me and a board in my hand. She was young once too, hair blonde rather than white, eyes blue and sharp, with a board to match mine. We spent two years on beaches, moving to follow the sun. I did odd-jobs, labouring, carpentry, picking if there was anything to pick. She waited, mixed drinks, made beds, cleared dishes.

I flick through more pages. There’s us in snow, us in deserts, us in cities. Then, all too quickly, there’s me in a suit and her in a dress, and something small in a bundle. Something small that hurts my chest, and causes me to close the book, to put it back in the drawer. I sit on the bed, and take a breath. I release, and take another. I release, and take another. And it’s not enough.

The room is as close as we could keep it, but everything is closer together now. The drawers don’t open all the way as they’re crowding the mattress and the rug is partly under the bed frame. On top, the covers are faded and the pillows are grey, but they’re just the right level of messy. The posters are still loud and the light is still incandescent, and when I load a cassette into the radio the sound still comes out just right. I can almost forget we’re thirty years on. I can ignore the phantoms in my hips and in my head.

She finds me here sometime later and she joins me on the floor. We sit until the sun dies and my ritual calls.

I find myself in the alley, a whole fifteen steps deep before I realise what I’m doing. Before I realise where she’s taken me. This isn’t the store, and I’m not here for groceries. I turn back, but the car is gone and I’m not a walker.

Each of the eight steps jolt my knees and my hips. They never healed right, not in thirty years. The third and fifth are taller than they should be and they throw off my gait, spiking hurt in my joints. The last one is cracked and broken. At the bottom, my sneakers settle in a centimetre of water from yesterday’s rain, and a little bit splashes through mesh and into my sock. The water is cold.

I finger the card — still in my pocket — and knock on the door before I can stop myself. My fist strikes two timber boards, narrow, and white, before striking again. In between breaths I look at my hand, at my white knuckles, and unclench.

“Yeap,” someone calls from within, “It’s unlocked.”

I look at the door, look at the knob. It’s brass, with a ring of knurling, and a dent on one side, and no keyhole — that’s set old-style, underneath. I grab, twist, and push.

The smell hits first: timber, iron, and coffee. The air is warm, but there’s a slight breeze from ahead of me, encouraging the door closed. When my eyes adjust to the light, my breath catches.

Joshua was born small, only five pounds, and he was born ill. I didn’t sleep for five months. Every day was the same: work wherever I could, go to the hospital, go home. Every day the news was different — he’s doing better, he’s doing worse, about the same. When he finally made it home, she and I just sat and looked at him for hours. Sleeping, like a normal boy.

At three, they called me into kindy. Another kid had kicked over Josh’s sand castle, so he’d pushed the kid over, but they’d hit their head. I told him that he could never do that again, no matter what they’d done to him. And we moved him to another place, then another, then another.

At school he had a hard time. Reading came naturally — we’d always read with him — but his little hands couldn’t make the letters the right way, and numbers were worse. At thirteen he was streamed into the bottom class, and gave them hell. Except for one class: hard materials; where the room smelt of timber, iron, and the teacher’s coffee. I went there when he died, once I could walk again. To give that teacher my thanks.

Benches are set all around the room, most with something on top: a drill press, a half-made bird house or garden bench, a set of taps and dies next to a disassembled appliance, a box of fittings, tubes, and pipe. Against the far wall, eight men sit around a pair of fold-out tables screwed into the floor: temporary made permanent. One brought his own chair, another has soda-can glasses, three have less hair and rougher skin than I do, and the others have physiques that’d humble a barrel.

“What’s your name, buddy?” One says, rising to hold out his hand. He’s a barrel-type, with a thick moustache and a red nose.

I find that I’m deeper in the room than I thought, and accept the shake.

“Herb,” I say, “The missus dropped me off.”

“Well, good timing Herb, I think there’s still some in the pot. Blonde or black, with or without legs?”

“Blonde, no legs,” I say.

The man in his own chair laughs and raises his hand to speak.

“That’s what I said,” he says easily.

Half laugh and half sigh, and one pushes a chair out to me.

“You work, or retired?” another asks. I realise that he has a name tag. His name is Michael.

“Ah, semi-retired,” I say, “I do a few days a week in a packing plant.”

He nods, “Thought so. I’m an ex-sparkie, did some work in there a few years ago before I finished up.”

An expression passes over Michael’s face as he continues.

“It’s a hole. More dead wires than live, and none of them are labelled. Last time I was there I fell through the ceiling and called it quits.”

“You punched that hole in the plant room? It’s still there. We taped cardboard over it.”

Something happens in my chest, and I realise it’s a laugh. Michael chuckles too, and the others join in.

Leave a comment